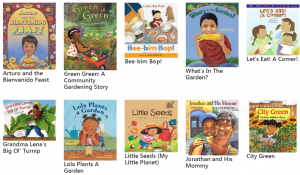

The Food Trust is recognizing Multicultural Children’s Book Day with the release of a list of over a hundred books with farm to ECE themes that feature characters from Black, Latinx, Middle Eastern/Arab, First/Native Nations, Asian, and multiracial backgrounds. The Food Trust’s multicultural collection of farm to ECE books highlights children’s books that feature characters from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, many of which are authored by writers of color. The list also includes a number of books that are either bilingual English-Spanish or written exclusively in Spanish and covers a wide variety of farm-to-ECE-related topics including gardening, farms, cooking, family meals, farmers markets, shopping for food and more.

We are also marking Multicultural Children’s Book Day with a critical reflection on the need for such a list. Children of color constitute a growing proportion of our youngest learners. In 2014, students of color became the majority in U.S. K-12 public schools, and children of color currently make up a majority of children under age 5 in the nation. Furthermore, a large and growing share of children under age 5 in the U.S. have a first language that is not English, and the proportion of emergent bilingual learners enrolled in ECE programs is growing across the nation.

Many children’s books, however, do not reflect this rapidly shifting demographic reality. When the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison looked at 3,200 children’s books published in the United States in 2016, it found that only 22% had people of color or Native/First Nations characters. Through a flurry of press in the mainstream media, a grassroots campaign called We Need Diverse Books has brought increased attention to the need for literature that reflects and honors the lives of all young people. And fortunately, conversations about representation in children’s books are extending beyond looking solely at the diversity of characters within books to also focusing on diversity of the authors behind the books. According to children’s book publisher Lee & Low, data collected in 2016 showed that roughly 80 percent of children’s book authors and illustrators, editors, execs, marketers, and reviewers were white. In addition, the majority of multicultural children’s book titles continues to be created by white authors and illustrators. In fact, in 2014, 57% of books published about people of color were written or illustrated by white authors. As Lee & Low’s director of marketing and publicity, Hannah Ehrlich, wrote in her piece on the diversity gap in children’s publishing:

It’s disconcerting that more than half the books about people of color were created by cultural outsiders. Realistically, these likely mean that there are more white creators speaking for people of color than people of color speaking for themselves. This problem may stem from a long history in which people of color have been overlooked to tell their own stories in favor of white voices.

The issue is even more pronounced for books featuring African-American characters. In 2016, only 71 of the 278 (25.5%) books about African-Americans were actually written and/or illustrated by African Americans. Melissa Giraud, co-founder of EmbraceRace, a community of support focused on race and raising kids, wrote in her blog post “Where to Find Diverse Children’s Books” about the harmful impact of stereotypical depictions and pathological narratives found even in some “diverse” books, usually those written by cultural outsiders:

Here’s the thing about “diverse” children’s books: some of them are not so great. You know, the books about Native Americans that lump them together, idealize them, put everybody in teepees, get the history wrong, and more. Books about Asian Americans in which everyone’s an alike-looking, broken-English-speaking foreigner. And the huge disproportion of books about black and Latino families in which everyone’s poor and life’s a never-ending struggle! Many are good, quite good. But the near single-storying of black and brown people also feeds harmful stereotypes and denies the diversity of our experiences and the fullness of our humanity.”

A new hashtag #OwnVoices is bringing more attention to children’s books written by authors who share a marginalized identity with the protagonist. Created by Corinne Duyvis, senior editor and co-founder of Disability in Kidlit, #OwnVoices is all about amplifying the voices of folks with marginalized identities to tell their own stories. When an author shares an identity with the characters they’re creating, they are more likely to craft an authentic and nuanced representation. These “counter-narratives” or “counter-stories” can challenge the dominant discourse about groups and individuals with marginalized identities. 20 years ago, before hashtags even existed, children’s lit author Jacqueline Woodson wrote an article entitled, “Who Can Tell My Story,” a powerful reflection on what it means to be able to tell our own stories and build bridges to other experiences that are connected to our own:

As publishers (finally!) scurry to be a part of the move to represent the myriad cultures once absent from mainstream literature, it is not without some skepticism that I peruse the masses of books written about people of color by white people. As a black person, it is easy to tell who has and who has not been inside “my house.” Some say there is a move by people of color to keep whites from writing about us, but this isn’t true. This movement isn’t about white people, it’s about people of color. We want the chance to tell our own stories, to tell them honestly and openly. We don’t want publishers to say, “Well, we already published a book about that,” and then find that it was a book that did not speak the truth about us but rather told someone on the outside’s idea of who we are.

Jacqueline Woodson’s words still resonate today. Leaders like Chemay Morales-James, a mother and educator who founded My Reflection Matters, are continuing to turn an important spotlight on the need for books that not only reflect children of color but also “mirror and affirm their rich, lived experiences [which] are often left out or narrowly represented/misrepresented in mainstream curricula and media.”

Children’s books, using children’s literature scholar Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop’s famed metaphor, serve as “windows, mirrors, and sliding doors” that allow children to read themselves into their own cultures and the cultures of others. Books that depict positive, authentic and nuanced depictions of children of color are a powerful vehicle for centering these children and their experiences. It is important to emphasize that, as Dr. Sims Bishop says, “the diversity needs to go both ways.” All children should have books offered to them that depict the rich variety of experiences lived by people from all backgrounds, not just those of people who look like them. She shares, “It’s not just children who have been underrepresented and marginalized who need these books. It’s also the children who always find their mirrors in the books and therefore get an exaggerated sense of their own self worth and a false sense of what the world is like because it is becoming more and more colorful and diverse as time goes on.” In other words, children from the dominant group benefit from experiencing counter-stories that decenter whiteness and affirm the experiences of people of color and First/Native Nations. As Sam Bloom shared over at Reading While White:

The idea behind Dr. Bishop’s work is simple: all young readers need more books with characters of all ethnicities and backgrounds, having a diverse range of experiences. This doesn’t mean that African American children only need to see more books with characters like themselves (although obviously they do), or that Ojibwe children only need to see more books with characters like themselves (might I add, in the present tense), and so on; but that African American children need to also see those Ojibwe characters, and vice versa. And also, children from non-marginalized groups (read: white kids) need to see these aforementioned books too. When white kids see white characters all the time, they get a distorted view of reality. White kids are overwhelmingly seeing “mirrors” but not “windows,” and that’s a huge problem.

In 2015, the book-review journal Kirkus started mentioning the racialized identity of main characters in all the children’s books it reviewed. It had been commonplace for decades for reviewers to include racial identifiers for characters of color, particularly if a book dealt in some way with race. The move to begin also identifying characters as white went against a long held English language literary tradition, which from its inception had assumed that both audience and characters were white unless otherwise stated. Kirkus’ shift in practice was done to reflect the fact that a large proportion of the audience for children’s books were people of color, that not all its book review readers were white, and ultimately, as Kirkus stated, to challenge the notion of white as the default.

Gloria Ladson-Billings, a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s School of Education who coined the term culturally relevant pedagogy, identifies the first step in becoming culturally competent as understanding one’s own culture. She shares that her mostly white student-educators usually find the the idea of unmasking white identities to be challenging and uncomfortable at first. In the book Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning in a Changing World, Ladson-Billings wrote, “I often explain to my students that due to social power dynamics that define whiteness as the unmarked, invisible norm, they are like fish who have trouble seeing the water that they swim in.” As we witness the cultural and demographic transformation of our society, it becomes increasingly important to contest the binary schema that places white on one side and “diverse” on the other. Decentering white and according it “just another place in a diverse racial and ethnic mix” may be a disconcerting concept for some from the dominant group, often due to the “unwritten standard of behavior in white culture that says…do not name race.” However, doing so is important because it opens up the opportunity to problematize the practice of framing multicultural education as merely learning about “other cultures,” rather than approaching it as also uncovering and understanding one’s own cultural identities. As Mariana Souto-Manning shares in Multicultural Teaching in the Early Childhood Classroom: Approaches, Strategies, and Tools, Preschool-2nd Grade, “We are all cultural beings, and it is important to identify the cultural threads that make up the fabric of our own selves. Unless we come to understand how our culture shaped and continues to shape who we are, we will not be able to teach multiculturally – we will continue to honor our own culture as the norm, and teach in (mono)culturally specific ways.” This also includes recognizing that all cultures are dynamic, not static, and that there is great diversity and multiplicity within all cultural groups, not only the non-dominant ones but also within the dominant one. When we as adults take this step, we can pass this new way of seeing and being on to the children in our lives. And when the children in our lives are given the opportunity to develop racial literacy, supported in their natural color-awareness, and given the opportunity to see how they belong to various cultural groups, they are more likely to grow up with positive racial identities, an ability to recognize racial inequities, and with the tools they need to stand up for racial justice. For more guidance of talking about race with children, check out the Raising Race Conscious Children blog and this great article in Young Children from the NAEYC.

The Food Trust’s collection of books, which will evolve over time to include more titles, is a resource that we hope will be useful to for all types of child care and early learning programs engaged in farm to ECE activities across the nation. As we share this list, we are imagining a future where book collections like ours, ones that reflect the growing cultural pluralism of our society today, become the norm.

Multicultural Children’s Book Day 2018 (1/27/18) is in its 5th year and was founded by Valarie Budayr from Jump Into A Book and Mia Wenjen from PragmaticMom. Their mission is to raise awareness of the ongoing need to include kids’ books that celebrate diversity in home and school bookshelves while also working diligently to get more of these types of books into the hands of young readers, parents and educators. #ReadYourWorld

Resources for Learning More:

- Selecting and Using Culturally Responsive Children’s Books

- Reading Your Way to a Culturally Responsive Classroom

- Talk, Read and Sing Together Every Day! The Benefits of Being Bilingual – A Review for Teachers and Other Early Education Program Providers │ Spanish (español)

- How to Use Bilingual Books│ Spanish (español)

- Selecting Culturally Appropriate Children’s Books in Languages Other Than English │ Spanish (español)

- Guide for Selecting Anti-Bias Children’s Books

- Talking About Race in Children’s Literature: Commentary and Resources

- Including Children’s Home Languages and Cultures

- Independent Presses

- Lee & Low Books: the largest multicultural children’s book publisher in the country, which is also POC owned.

- Resources for Books in World Languages

- Diverse Book Finder, Disability in Kidlit, Diversity in YA, Latin@s in Kid Lit, Rich in Color, Gay YA, American Indians in Children’s Literature, SLJ’s Islam in the Classroom, ALA’s Rainbow List, SLJ: Libro por Libro, Vamos a Leer, Jewish and Muslim MG/YA/NA Authors, LGBTQIAP+ Books By Authors Who Identify as LGBTQIAP+, Trans-Identifying Authors, Africa Access Review, The Brown Bookshelf, We Need Diverse Books, Reading While White

Multicultural Children’s Book Day Reviews*:

- Todo es canción: Antología poética (Spanish Edition) by Alma Flor Ada

- Poesía eres tú: Antología poética (Spanish Edition) by F. Isabel Campoy

- No Kimchi For Me by Aram Kim

- Arturo and the Bienvenido Feast

*We received these books for review as part of Multicultural Children’s Book Day